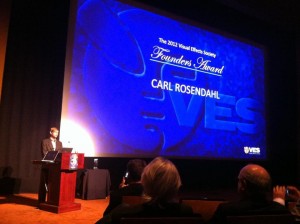

Writing is a very painful thing for me. I fret over words and structure, over ways to express my ideas clearly. The speech I gave accepting the Visual Effects Society’s Founders Award was particularly challenging, it was important, deeply personal, and directed towards potentially 3,000 of the most talented and creative people in the visual effects industry.

In this post I break down the process I went through, and take apart the speech paragraph by paragraph to show my thoughts and structure behind it. This isn’t about the content per se, but about the methodology I used and a few breakthroughs I had along the way. I’m doing this as a learning exercise for myself, but you’re welcome to tag along.

If you’d rather just read the transcript, that is here.

The Setup

In May, Jeff Okun let me know that the Board of the VES had awarded me the Founders Award, to be presented at the Annual Membership Meeting in September. I was (and am) deeply honored to be the recipient, but I also had a brief panic attack – after accepting the award, you are given the floor for about ten minutes. Jonathan Erland, the first recipient in 2006, made an incredibly moving and inspirational speech to the Society, setting a high expectation for all of us who have followed. I didn’t want to screw that up.

Now, four months later, I have delivered that speech. It is one of the most difficult talks I’ve ever written – not because of the subject matter, I knew right off what I wanted to say – but because I wanted to vent some of my frustrations with the effects industry while still ultimately being inspirational.

The Goal

The VES includes members from across the visual effects spectrum: movies, television, animation, commercials, games, even some corporate work. It is also an international organization, with members from 29 countries. But by the nature of its demographics and its initial DNA from the founding Board members (of which I am one), the society is somewhat LA and movie-centric; and the movie industry right now has some serious issues that are dragging the Society down.

I wanted to pull people out of their self-pity holes and inspire them to keep inventing and creating amazing things. I’ve always had a forward looking approach to life and business, so that was my natural direction with this talk.

The Rough Draft

I was invited to be a keynote speaker at the SIGGRAPH Business Symposium in July which I accepted, mostly because I knew I could try out some ideas for my VES talk in front of a similar, but much smaller and non-recorded, audience.

That talk was adapted from one of my Entrepreneurship classes about lessons I learned building PDI. I expanded it to include my venture capital career and what I’ve learned from teaching at Carnegie Mellon. The last five minutes of that 35 minute talk became the foundation for this VES speech – I’m frustrated with people in the industry whining about the state of the industry and not being visionary anymore. The list of issues in this talk (outsourcing, tax incentives, global competition…) were taken directly off 3×5 cards that audience had filled out earlier in the day about their concerns.

Ideation and Purgatory

For the month after that I wrote down notes or whole paragraphs from ideas I’d have. This percolation stage is important for me, I may discover a few themes but mostly I argue with myself about ideas – do they really make sense, would I be able to defend them? I also notice interesting snippets in articles and conversations that work their way in. I pulled elements out of other talks I had given and rewrote them in the context of my goal for this talk.

For the month after that I wrote down notes or whole paragraphs from ideas I’d have. This percolation stage is important for me, I may discover a few themes but mostly I argue with myself about ideas – do they really make sense, would I be able to defend them? I also notice interesting snippets in articles and conversations that work their way in. I pulled elements out of other talks I had given and rewrote them in the context of my goal for this talk.

Then I got stuck in Purgatory. I had reams of material but didn’t know what to do with it. I felt like it was all about to go to hell, but somehow it didn’t. Nor did it lift itself higher.

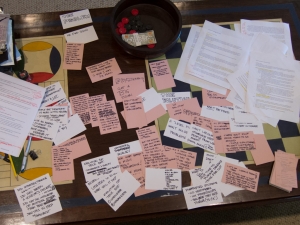

The panic set in once again. I had a lot of pieces but no theme or structure. I would begin writing drafts that would bore me halfway through. I transcribed the relevant sections of my SIGGRAPH talk (I had a bootleg recording of it!), which only added to the mess. So I decided to go completely analog. I took each snippet of an idea I had and put it on a 3×5 card. I printed out all the drafts I had done, highlighted each main idea and wrote them on cards. Then I spread them all out. I collected cards into themed groups, trying a few different algorithms to define the themes.

Breakthrough

The card groupings started to make sense and I could begin to see a structured argument, a flow. It was a simple introduction, a statement of the problem, some solutions, and a pile about my students which I though provided some youthful inspiration. To the side was a pile of thematic cards – the impact of Moore’s law 20 years from now (from my SIGGRAPH talk), the tension between convenience and quality (from a talk I gave in Korea), the evolution of entertainment technology (from the same talk in Korea).

I decided to dig deeper into the evolution of entertainment technology as a framework to hang everything else on. I reworked the timeline I had made before and added more about music to it, but this time I went farther back and looked at orchestras as a form of destination entertainment. Bingo. I was amazed to see the growth and evolution of orchestra size, and how closely that paralleled movie theaters. And that’s when I found my 1920s musician analogy.

With a real theme to work with I wrote more cards to fill in some gaps, stacked them up in order and started writing. This time it flowed.

The Final Structure Change

The script was pretty linear. Intro, state the problem (my frustration with the industry), walk through the history to set up the analogy, talk about short term solutions, and then talk longer term about building out a vision. I read it to my wife and it went over pretty well, but something was nagging at me.

I realized I had a theme (the orchestra) but I didn’t have a structure – the whole thing just walked a straight logical line. So I decided to see if I could put it into a three act structure – the idea seemed appropriate for my audience.

Act I would introduce the characters (me, the audience, and the effects industry) and a conflict. In this case the inciting incident is my frustration with the audience thinking the industry is dying.

Act II was more difficult to figure out. Our characters need to fight some battles and win, building up confidence, which then gets challenged with the surprise climax leading into Act III.

This is where I decided to break my history trip into two parts. I left out our major antagonist, the Internet (a representative of even greater technological change ahead), and made the battle more about the orchestra vs. the movie and TV industries. Now I could talk about some ways to approach the current issues and hopefully help our audience win some battles. They might even feel good about themselves.

Then I could end Act II with a bigger, tougher challenge: new technology comes in that makes the prior battles insignificant. This is done through visiting our history trip again, but introducing the character that I failed to mention before. This time I also armed our audience with the technology and creative skills they seemingly didn’t have before.

I also cast my students as either villains or heroes in the final act, depending on whether the audience sees them as a threat or as a part of their team.

I don’t reveal the ending to the story, because it hasn’t been written yet. I leave the audience with the challenge of finishing it themselves.

I love the changes that the three act structure gave to my talk. The audience gets to go on a ride now with some emotional ups and downs rather than just listen to a linear argument.

And now, the talk…

Below is the talk with notes embedded about specific choices I made in wording and how I hoped those words would affect the audience.

Act I: The introduction; in which I hope to establish credibility without taking credit for inventing everything. I didn’t introduce the audience or the effects industry explicitly; I believe that was implicit from the context of the evening. If this were given to a different audience I would expand out this part.

I am privileged to be a part of an industry and company that helped change the world. When I started PDI in 1980, I joined a small community of people who believed that we could make something that was impossible to do at the time – that someday computers could be used to create images to tell stories on TV and in the movies. We knew it would take a long time, maybe 15 or 20 years to do.

The 20 years number is important here. I tie back to it near the end of the talk.

We caused a fundamental shift in the way films are made and the types of stories that can be told. We did this with a passion for inventing, for building and wrestling with the technology until we could conform it to our will.

I’ve also had the unique opportunity to have had 3 different careers around this dream:

– As an entrepreneur helping to create and build an industry

– As a VC investing in entertainment technologies

– And now as a professor mentoring the next generation of creative talent

Having established credibility and background, it’s now time for the inciting incident.

So it’s disheartening to me to see the industry I love so much behave like it’s dying, when in fact it is just being born.

Hopefully people just got a jolt and I’ve gotten their attention. I’m mad at the industry, and thus the audience. I’m also optimistic.

I wish I was 23 again!

This line is a ruse. It seems to be there to underline my optimism about our industry, but it’s really there to reinforce the fact that I started PDI when I was young. This will hopefully echo a bit at the end when I talk about my students as future competitors.

Act II begins. It’s story time, leaving the audience hanging about my frustration.

To understand my frustration, let’s take a quick trip through time, starting in the early 1800s, and look at what our options for entertainment are.

It’s 1820; we can read, socialize, play games and music, and dance with each other. We can create and enjoy art – paintings, drawings, sculptures. We can go out to hear live music, including classical orchestras with 35 musicians.

Planting the orchestra theme right at the beginning.

Photography is invented in the late 1830s, and by the mid-1840s becomes a popular way to record images of ourselves, our environments and our daily lives – dealing a blow to painters, who react by exploring their medium in new, more interesting ways.

Most of this audience should be familiar with the birth of impressionism, etc. I am also leading the audience here with the idea that when your industry is “dying” it might really be just getting born.

Orchestras continue to be popular, and composers start to make them bigger, swelling to twice their former size – a trend that lures bigger audiences and creates larger concert halls.

From the little user testing I did beforehand, the analogy to movie theaters seems to already resonate here.

In about 1878 both the phonograph and moving pictures are invented, and by the late 1890s they start to vie for people’s attention listening to music at home and watching Kinetoscopes in penny arcades.

Perhaps not coincidentally, composers like Wagner and Stravinsky expand the size of orchestras to almost 100 members, creating huge, loud, exhilarating experiences to attract their audiences.

The analogy most certainly resonates here. Hopefully people are imagining large theaters with spectacles in play.

In 1906 the first radio program is broadcast, ushering in a new era of live entertainment delivered directly into the house, followed closely by the birth of Hollywood enabling the motion picture industry to thrive.

Hooray for Hollywood!

And orchestras get bigger. By the mid-1920s they hit their peak size of 110 to 120 members.

“Peak” is a clue, I suspect most of the audience has figured out by now where I’m going with this. Hopefully they are even thinking exactly about that.

Then, in 1927, The Jazz Singer is released – the Talkies are born,

The Jazz Singer is the inciting incident of my thesis, a play within a play if you will.

and the role of the orchestra changes forever.

… and the audience feels like they are smart for having figured it out before I said it.

Now I need a bit of exposition to make my point about orchestras stagnating, as there is a much bigger transition going on. This part is straight from a talk I gave in Korea a few years ago about convenience vs. quality – the consumer will always sacrifice quality for convenience, but ultimately they demand both. An earlier draft of this talk went into detail about that, but it doesn’t matter, so it got cut. Also, “Philo Farnsworth” is just fun to say and hear.

But the movies haven’t won. A year later, in 1928, Philo Farnsworth invents the television and the war for the moving picture audience begins. Movies add color. TVs add color. Movies get bigger. TVs get bigger. Movies add surround sound. TVs add surround sound. Movies get even bigger. TVs get even bigger. They both go 3D. Movies go onto TV. TV goes to the movie theater. Movies add a higher frame rate. TV already has it.

Our orchestras in the meantime have stagnated. Their traditional performances are funded as much by charity events as they are by ticket sales.

The audience knows that they are the orchestra, and now are picturing their futures funded by old people in tuxedos and gowns longing for the day of the theatrical experience.

The musicians spend much of their careers performing music that is the score behind the motion pictures made by the industry that sidelined them.

“Sidelined” is used here to point out that orchestras aren’t dead, but they don’t have the importance they used to for the mass audience. That word is used again later as a threat.

But that isn’t to say that those changes were bad for music. Those same broadcasting and recording technologies created a new music industry that gave birth to jazz, rock and roll, and down tempo trip hop techno pop.

And a bit of optimism here – all that technology that sidelined the orchestra opened up a lot of new opportunities for artists, like the painters mentioned earlier. I would have loved to have dwelled on this part, too. The audience may see that it implies new opportunities for them, also.

Today, you’re the musicians in that orchestra in the 1920s. There are big changes happening that you can ignore or take advantage of.

They have figured this out, and are presented with the challenge.

The only issues I hear about are outsourcing, tax incentives, global competition, unfair business practices, runaway production, trade organizations, unions, ownership, piracy, the race to the bottom.

When read aloud, this list is very long and tedious. “Race to the bottom” is a term that I hear a lot, and also sums up the list very well.

It’s really important stuff; I understand that, I’ve run a business.

There is no solution, only opportunities.

This upcoming section is a windmill. We will fight it, but find out later that it doesn’t matter. I anticipate that by the end of this section people have maybe seen a few things they can do, but overall are somewhat disappointed that I wasn’t going after anything more interesting – that’s fine because I have a surprise in store. I’m not sure the ordering is optimum, but I tried to order them from reactive to proactive.

If you think a trade organization will solve your problems, then get off your ass and make one. Start small, pick an easy problem and fix it. Grow from there to bigger, harder problems.

I believe this. C’mon people, do it already. I had a lot more to say about this, particularly in the context of the VES, but it wasn’t germane to this talk so I cut it out.

A “level playing field” won’t solve all the problems. You can’t legislate or otherwise keep people from willingly losing money.

I could have gone off on this one for a while, too. It was very difficult to force myself to be brief. Again, this is a windmill, not my main point.

Getting participation won’t be free. You have to put skin in the game, and in Hollywood’s case, skin is cash.

Globalization: It’s here to stay, deal with it.

Diversification gives you a broader base of business. You can invest in change that way without even having to go all in.

I like the next two paragraphs a lot; they tie in to the bigger picture about doing something different from everyone else. If I wasn’t trying to tie up the ending of the talk in a small succinct package I might have moved this there. I’d love to talk more about “commodity” because the VFX industry hates being called that, for good reason, but I understand why so many clients think of it that way.

There isn’t enough movie work to go around. It’s simple supply and demand. You can’t limit the supply of companies willing to do the work; in fact it’s still growing. You need to create demand for something that you can do better than anyone else. And not just better, but you need to be unique.

The only way you’re going to convince your customers that you’re not a commodity is by being able to offer them something no one else can. If you’re offering the same product with the same terms, then as far as they’re concerned you are a commodity. You have to be different to compete.

I went back and forth about whether to include this whole DD section or not, right up to the time I walked on stage. It really is tangential to the talk, and if I ever give the talk again I would cut it out. I left it in, though, because it’s so topical at the moment and I’m guilty of the distraction myself. I am going to do some user research to see what the audience felt about it.

Digital Domain has been a voyeur’s delight, but don’t get too distracted by it. There is only one lesson to learn there, and it’s a general life lesson not a VFX lesson: don’t spend money you don’t have. DD is not a specific indicator of anything wrong in this industry other than that company’s bad management. We saw this happen before in 1987 with Omnibus – they went public on the Canadian stock exchange, then gobbled up two other companies that were struggling, with the hope that even though they were losing money they’d make it up in volume somehow. That also lasted less than a year. But great companies like R&H rose up out of those ashes and did it right.

DD’s strategic thinking wasn’t necessarily wrong, but its implementation was crazy. Ender’s Game might have worked. Tembo might have worked. An animation school might have worked. Doing military contracts might have worked. But they only had the resources to pursue one of those things.

My recommendation: If you weren’t at DD, then don’t waste any more of your time on fretting about DD. Move on and dedicate your precious brain cycles to making things better for you.

And don’t spend money you don’t have.

So now we celebrate that we’ve destroyed the monster. Act II is almost over, we think we might be done.

So maybe you think you’ve fixed it. It seems there’s a level playing field, and while competition may be stiff, at least nobody feels like they’re getting screwed. The death of our industry has been averted, or at least postponed.

The bigger challenge is introduced. I left something out of the history section the first time, so we revisit it to find out that what we ignored was very important.

In my first good draft of this talk the history part was all one section. Breaking it into two pieces was what finally unlocked the structure of the talk for me.

But let’s go back to our history field trip. It’s the late 1960’s and life is good.

While the movies and TV are duking it out, groups of researchers under a government contract are figuring out how to network computers together and in 1969 Southern California and Northern California talk over the ARPANET for the first time.

I used “groups of researchers under a government contract” to add some conspiracy flavored tension. It is poetic that the first message over the ARPANET was between Southern California and Northern California – Hollywood and Silicon Valley – I love it. Perhaps I should have used those terms instead.

Jump forward a bit to 1995, the year the DVD is introduced, and the Internet is set free upon the world, becoming officially commercialized.

The DVD line is there to anchor it in the movies/TV war, convenient timing.

This extra piece of information completes our history trip, so we go back to the opening statement about what our options for entertainment are to compare them.

So now again, we find ourselves in 2012. Our options for entertainment and idle time amusement seem endless. The music we used to have to go to the concert hall to hear came directly into our houses with the advent of radio. The transistor radio made that portable, and the Walkman allowed us to select our music while on the move. Now because of the Internet we can choose from millions of songs and have them streamed instantly to us anywhere, anytime in glorious high fidelity. That’s happened with video, movies, and even with our old friend the book.

Now, we can read or socialize. We can create, share and enjoy music, photos, videos, television and movies. We can play games alone, we can play games with friends, or we can plan in a clan against 1000s of other people. We can blog, tweet, follow, unfollow, friend and unfriend. Anytime, anywhere.

Hopefully overwhelming, but just in case you didn’t get it, here’s the one sentence version:

That’s a lot of competition for our free time.

And from that I make a statement that I hope bothers people…

It astonishes me that people keep going to the movies at all.

Ouch. I just told the audience that their work isn’t interesting. But then I explain why it is.

But they do because the experience keeps getting bigger and more extreme – which it must do to compete with all our other activities. Movies have to give us magic we can’t experience in any other way. And that’s what visual effects do, and why every major film depends so heavily on what we do. They have to. Go big or go home; or go mobile.

I tie the path of the movie industry to exactly the path we saw orchestras go through – bigger and more extreme – and why they have to do that. I also give some kudos to the visual effects industry for being what keeps Hollywood in business.

And that takes us to my major point, that the world is changing and the movie industry isn’t. I had a whole tirade here about Moore’s law and computers being 1,000,000 times better in 20 years, but cut it all out – the point just needed to be made concisely.

But I don’t believe that’s sustainable. All those other options will catch up. High end game experiences are becoming cinematic and letting us into the action. The march of technology will create dozens of more options for the audience. Inputs won’t be limited to mice, keyboards and touchscreens – gestures will be common place along with advanced biometrics. And that high end experience is going to go mobile with higher resolution and better displays that eventually will beam directly onto our retinas without the need for a screen. Seriously.

The next line is for clarity. Entertainment is becoming more important, but movies aren’t.

Entertainment will become integrated even more tightly into our lives. But not as movies.

I went back and forth on taking the “disruption” line out. It’s a good word to use, but probably didn’t add anything to the talk.

That’s called “disruption.”

It’s time to lay out the challenge. Here I use the same words as I used for our windmill. We’ve been here before…

Right now you’re still the musicians in that orchestra in the 1920s. There are big changes happening that you can ignore or take advantage of.

Then I added in the other part that I left out: you have power you didn’t have before.

But this time, you’re sitting on the technology and creative skills that will help define the entertainment experience for the next century.

“Next century.” I wanted this to be very forward looking, and a century is a reasonable timeframe. It also ties in well with the time span of our history trip.

More repetition. Yep, been here before, too.

And still, the only issues I hear about are the same ones: outsourcing, tax incentives, global competition, etc.

Some tough love now follows. This is the climax event if you’re looking at this as a three act structure. Everything we’ve gone through is at risk.

I’m also bringing the time frame down to twenty years. This makes it a comprehensible time frame for an individual, and ties back directly to my opening statement that we thought it would take 15 to 20 years to build our industry – proof that amazing things can be done in that time frame.

Twenty years from now it does not matter. At all. Because twenty years from now the business that you’re in today isn’t going to be relevant. If you don’t change and figure out what your new business is, then you will be sidelined.

“Sidelined” again to echo the orchestra’s fate. Finally we get back to understanding my frustration that was the initial conflict.

So here is my frustration: Where is that vision? Who’s looking ahead and talking about what they’ll be doing in the future that’s impossible today?

It’s time to wrap this up pretty succinctly, being Act III and all. So, with apologies here to my students, they are packaged as the final threat that you didn’t see coming. The audience can interpret them as villains or heroes.

I care about that future.

My students do, too. And they are your current audience; they are your employees; and they are your future competitors. They have a big vision for their future, and they will make it happen.

I bring up a couple of points that aim at the complaints mentioned before.

My students are from the United States, Canada, Venezuela, Columbia, France, Spain, South Korea, Singapore, India, and China. That’s this semester. If you’re xenophobic, or are a protectionist about your community, state, country, continent, or hemisphere, you can learn something from them. They’re smart, they embrace their multi-cultural experiences, and they work together easily despite the seven (or more) native languages they speak.

To drive it home, you are sitting on not just the technology and creative skills, but you’re in the right place, too. (I realize my audience is global, and I’m trying to reinforce the global community with my talk, but my live audience is right in the heart of Hollywood so I address them directly.)

And here’s an interesting irony: like you, they all believe they need to leave their native countries to find work. But they want to come to California because that’s where the opportunities are.

Your business concerns are irrelevant to them. They want to follow someone with a great vision or they want to be entrepreneurs themselves.

They are thinking young.

They have time to pursue their dreams. They are thinking far into the future.

The final challenge. I don’t reveal the ending to our third act, it is up to the audience to resolve with their actions.

What about you? What’s your vision? What impossible problems are you trying to solve?

Are you going to be just a member of the orchestra playing the same old song, or are you going to stand up and be a part of the future of this industry?

Tied up with a final reference to the orchestra and a challenge to take action.

Here’s a secret: I thought that if I really nailed this talk I could get a standing ovation (which I did!), so I challenged the audience to stand up and be a part of the future of this industry – so A) I seeded the word (don’t know if that helped or not), and B) more importantly, by standing up, everyone is committed to take action now, and that is awesome.

Thank you.

You continue to be one of my very few heroes. Thank You.